“In my mind’s eye I had that boat destroyed,” he said. “I came around with pass after pass till I was out of ammo.”

Later on, long after the war was over, Hamner would find out that at least one boat hadn’t been destroyed. He also learned the convoy wasn’t Laotian, but Chinese, supplying the Viet Minh with troops and supplies. He had fired on the boat three months before Nixon’s historic visit to Beijing, ending years of isolation between the two world powers.

“Some of the maneuvers and things that I did usually provoke the Pathet Lao to shoot. The Chinese were disciplined, they were just holding fire til the helicopters came in,” he said.

Nobody, including the Chinese or the Americans, was supposed to be there.

The Ravens were FACs (forward air controllers), who along with Air America, waged the CIA’s so-called “secret war” in Laos.

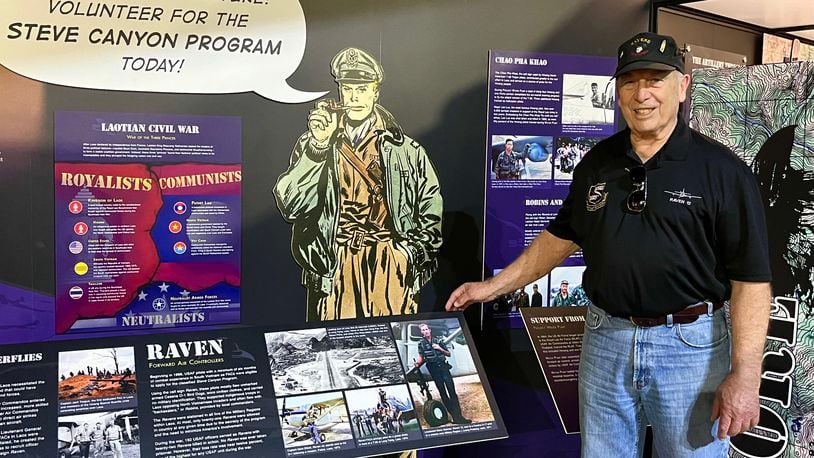

Now, much of the documentation associated with the force is declassified, and the Ravens now have a place in the National Museum of the United States Air Force, alongside other displays in the Vietnam War galleries.

Hamner, who now lives in Middletown with his wife, has worked to tell the Ravens’ story since the program was declassified.

“I’d do it again in a heartbeat. And I think every Raven that did it would say the same thing.”

Beginning in 1966, U.S. Air Force pilots with a minimum of six months of combat experience in South Vietnam could apply for the highly classified Steve Canyon Program, according to the Air Force Museum.

Hamner, after finishing officer training school with the Air Force, flew as a forward air controller in Thailand, before joining the Ravens.

On paper, Laos was a neutral country in the Vietnam War. A 1962 treaty signed in Geneva declared as much. However, the agreement was violated almost immediately by just about everyone involved, including the United States, the Soviet Union, China, North Vietnam, and the Pathet Lao themselves.

Over the course of the war, less than 200 Air Force officers were hand-picked to fly unmarked and armed Cessna O-1 Bird Dogs, the faster U-17, and the heavy-hitting “Cadillac,” the T-28, armed with .50-caliber machine guns and high explosive rockets. All three flew low, slow, and were highly vulnerable to ground fire.

“They got FACs out of Vietnam and they put us to work,” Hamner said. “We were freewheeling when we were there, we had very little supervision.”

These pilots, many of them Air Force veterans, flew in civilian clothes and wore no military identification, disrupting resupplies from Communist allies, and supporting friendly Laotian troops from the air.

Some Ravens carried a “backseater,” a Laotian who translated, talked to ground troops, and helped locate bombing targets. Others carried out missions to stem the flow of troops and supplies into Laos, providing tactical air strikes in support of ground troops, and reconnaissance.

“I would get up usually about an hour, hour and a half before daylight when we could fly,” Hamner said.

The Ravens would then check in with the Area of Operation Committee, which included them, the CIA, and allied Laotians. The Kingdom of Laos, sympathetic to South Vietnam and the United States, supported the Ravens.

“We would listen to what went on during the night. We’d listen to the Laotians, their commanders, and go wherever they had troops in contact, do visual reconnaissance or airstrikes as necessary.”

At most, only 21 Ravens were allowed in country at any given time due to the secrecy of the program. Over the course of the war, 22 Ravens were killed in action.

Hamner has returned to Laos three times.

“Just talking to people without fear of somebody eavesdropping on it, you’d be surprised how much they respected the Americans for what they were doing,” he said.

About the Author