"If they go down that road, it is a very, very difficult path," said John Ruple, an expert on public lands at the University of Utah College of Law in Salt Lake City.

In Utah, Gov. Gary Herbert and key members of the GOP delegation — including Jason Chaffetz, who heads the House Oversight Committee — want Trump to roll back the 1.35 million-acre Bears Ears National Monument, which Barack Obama created in late December. GOP leaders in Maine are pressing Trump to reverse another Obama conservation designation — the Katahdin Woods and Waters National Monument, created from 87,500 acres of donated forestland.

White House officials are reviewing the requests and haven't yet signaled whether Trump will challenge Obama's use of the Antiquities Act, which Roosevelt signed into law in 1906.

Yet Trump supporters continue to lobby the president to at least scale back what they call Obama's "midnight monuments." Herbert and others say they are working to quickly bring Interior Secretary Ryan Zinke — Trump's point person on public lands — to Utah, so he can help champion the cause.

"What is a concern for us is some president who with a stroke of a pen as he goes out the door ... runs roughshod over the people of Utah," Herbert said in a recent interview with McClatchy.

"We will work to repeal this top-down decision and replace it with one that garners local support," said Chaffetz, whose district includes San Juan County, where Bears Ears rises from the Colorado Plateau.

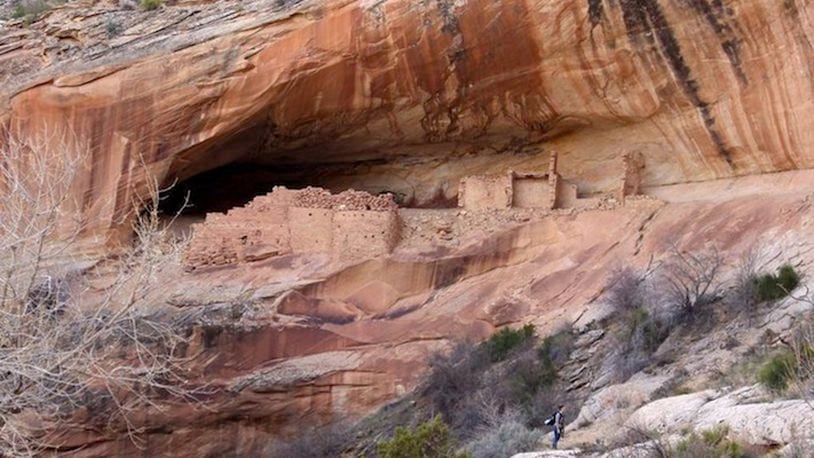

An expanse of federally owned forests and red-rock canyons, the Bears Ears monument is larger than the state of Delaware. Considered sacred by local tribes, the area was occupied by Ancient Puebloans, who left behind rock art and pottery now at risk of looting. The protected status of the monument still allows livestock ranchers to lease grazing land, but it restricts other activities _ including new mining, oil and gas development, and road construction.

Lawmakers in Utah and other states have fumed about previous monument designations. President Bill Clinton and his interior secretary, Bruce Babbitt, angered some Utah politicians by creating the 1.9 million-acre Grand Staircase-Escalante National Monument in 1996.

Several Utah counties sued to overturn the designation, but in 2004 a federal judge dismissed the lawsuit, ruling that Clinton had been within his legal authority in making the designation, even at 1.9 million acres.

In his 47-page ruling, U.S. District Judge Dee Benson called the Antiquities Act a "proper constitutional grant of authority to the president." He added that, under the 1906 law, courts cannot review whether presidents have abused their discretion in establishing monument boundaries.

Ruple, the Utah law professor, said he saw little legal grounds for Trump to overturn a designation made by a predecessor. "The Antiquities Act doesn't say anything about undoing a monument," he said. "It only talks about creating national monuments."

Under the law, presidents do have the authority to shrink the size of a monument, and some have used it, although mostly for minor adjustments. Two months before he was assassinated, President John F. Kennedy changed the boundaries of the Bandelier National Monument in New Mexico, adding about 3,000 acres and removing another 4,000, at the behest of the neighboring Los Alamos National Laboratory.

If Trump sought to shrink Bears Ears, he'd have to justify the decision by claiming, for instance, that the monument's boundaries were larger than needed to protect "objects," or antiquities. Conservation groups say they are already gearing up to respond.

"We will look to fight any kind of reduction in any venue we can, whether it is the court of law, the court of public opinion, Congress ... whatever it takes," said Nada Culver, a senior counsel with the Wilderness Society's office in Denver.

Tribal leaders, who had lobbied Obama for two years to designate the monument, said they'd also work to defend the monument's boundaries. Last Friday, members of a newly formed Bears Ears tribal advisory group sent Zinke a letter urging him to partner with them. The letter said that any attempts to rescind or shrink the monument would be "absolute tragedies in terms of impacts on our people today."

Congress passed the Antiquities Act amid widespread looting of archaeological sites in the Southwest and other parts of the country. In response, lawmakers granted the president authority to declare national monuments and quickly dispatch federal rangers and resource to protect artifacts.

Drafts of the legislation initially limited the size of a president's monument to 640 acres or fewer, according to Richard West Sellars, a National Park Service historian who wrote a 2007 paper on the Antiquities Act. The bill's authors later changed that language to allow presidents to create monuments "confined to the smallest area compatible with proper care and management of the objects to be protected."

Over the years, presidents have used the act to create expansive monuments, including ones at Grand Canyon (1908), Arches (1943) and Grand Teton (1943). All were controversial, said Ruple, but eventually they became some of America's most beloved national parks.

In Utah, the Trump administration and Congress could try to derail Bears Ears by withholding funding, and Chaffetz has already asked a House of Representatives appropriations subcommittee to do just that. But Culver, of the Wilderness Society, and other lawyers say the federal government could find itself in a legal pickle by refusing to honor a presidential monument designation.

"Now that we have a proclamation, that changes the game," Culver said. Bears Ears is now part of the Interior Department's National Conservation Lands, a designation, she said, that requires the federal Bureau of Land Management by law "to prioritize managing these monument objects above everything else."

About the Author