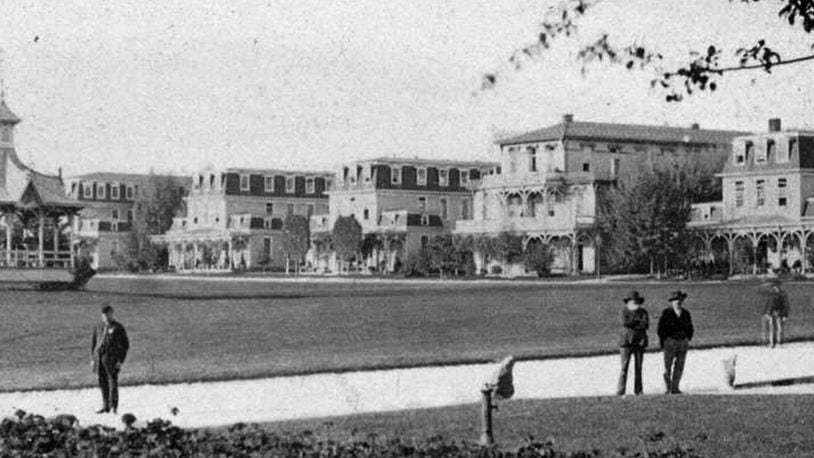

The answer: soldiers’ homes constructed on a scale unseen in America. Among the very first was built in Dayton. The campus became not only a destination for recovering soldiers, but for patriotic tourists who came from far away to pay their respects to the veterans and take in the spectacle of the ornate architecture and grand gardens.

The central branch of what became the National Home for Disabled Volunteer Soldiers on Dayton’s west side opened its gates to the first veterans in the fall of 1867, two years after the end of the Civil War.

The idea for the National Home, now known as the Dayton VA Medical Center, sprang from the United States Sanitary Commission, a group who oversaw the care of wounded Civil War veterans. The commission lobbied Congress to form an agency that would oversee the care of veterans. President Abraham Lincoln signed the legislation on March 3, 1865.

Credit: DAYTON VA ARCHIVES

Credit: DAYTON VA ARCHIVES

“It was a revolutionary idea,” said Tessa Kalman, archives manager and historian for the Dayton VA Medical Center. “This is the first time in the history of the world that a government decided that we want the best for our veterans.”

Lewis B. Gunckel of Germantown, considered the “Father of the Dayton VA,” was instrumental in locating the Soldiers Home in Dayton. Gunckel, who served in the Ohio Senate for four years, was secretary of the Board of Managers of the National Home for Disabled Volunteer Soldiers.

To be considered for one of the new soldiers’ homes, a site had to be near a large city, have fresh water and access to a railroad line. The 393 acres Gunckel proposed met all three criteria and was located three miles west of downtown Dayton.

Credit: DAYTON VA ARCHIVES

Credit: DAYTON VA ARCHIVES

Housing quarters were quickly built from loads of lumber hauled by train from Columbus. As soon as a three-story barracks was built, it was filled with waiting veterans who arrived in droves.

At its peak in the late 1800s and early 1900s, the Soldier’s Home housed more than 7,000 veterans. It had a farm, workshops, two churches and a school where veterans learned reading, arithmetic and penmanship. Physically able soldiers helped with the design of the grounds and the construction of the buildings. A hospital opened in 1870 and was regarded to be the best in the country at the time.

The home served as a sanctuary for the veterans after suffering through the devastation of the Civil War. The elegant campus featured a conservatory of palm trees and a fountain named “Water Waifs.” Lilly-filled aquatic gardens were heated to 80 degrees by steam lines from the conservatory.

Credit: DAYTON VA ARCHIVES

Credit: DAYTON VA ARCHIVES

A menagerie held foxes, a wolf and several bears. Alligators lived in one of the ponds and there was an indoor nursery for their offspring. More than 50 domesticated deer roamed the park.

The National Home and its amenities became a tourist attraction for the public. Over 660,000 visited the home at its peak in 1910. Railroads created special soldiers’ home picnic excursions. Visitors could catch a train from Cleveland and other cities and travel to Dayton for the day. They joined the soldiers in the gracefully appointed Memorial Hall for lectures and recitals. The French stage and film actress Sarah Bernhardt was a among the well-known performers who entertained guests.

“The soldiers loved to receive visitors,” Kalman said. “The people were very patriotic and wanted to come visit the veterans, thank them for their service and appreciate the beautiful place they built.”

The original mission of the Soldiers Home was to create a home-like environment for returing veterans and that mission holds true today, Kalman said.

After World War II, medical and VA system advances meant fewer veterans at the home. Today, only a few hundred live on campus, though almost 39,000 still travel to the grounds to get services each year.

About the Author