On Jan. 19, 1918, the U.S. Army Air Service formally chartered the Medical Research Laboratory at Hazelhurst Field on Long Island, New York, in part to help select aviators, train them and keep them safe. After less than four months, the laboratory graduated the first three aviation medical examiners, called flight surgeons.

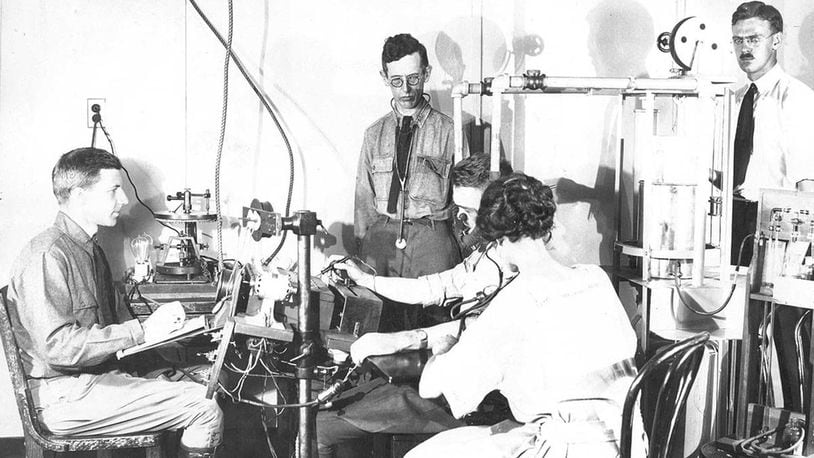

Original course work and research included experiments with low pressure chambers and the development of psychological profile tests. Over the next few years, the lab became the School of Aviation Medicine and, in 1926, moved to San Antonio to join the line of the Army Air Corps at the biggest flying training base. Their mission expanded from aviation research and training to include support of flight line operations and medical care as well.

New names continued through the decades until it eventually became the United States Air Force School of Aerospace Medicine, and the scope of the school’s mission continued to change, with research often taking a secondary role.

By the 1940s, the nation was building up to war again. Despite the initial emphasis, from 1919 to 1940 only 490 flight surgeons had been trained. Only a few years later, by 1943, the school had graduated more than 2,000. It also started training enlisted personnel who would assist flight surgeons and added altitude physiology for non-medical officers.

The school also saw a renewed emphasis on research, led by none other than Lt. Col. Harry Armstrong. When Chuck Yeager broke the sound barrier in 1947, Armstrong envisioned man in space and created the Department of Space Medicine, beginning the transition from aviation medicine to aerospace medicine. The first air transportable iron lung came out of that department, as did the development of the respirator.

For the next decade, the school led the nation’s space research. Though much of that work faded as NASA was developed, the school still played a critical role, from working with the initial astronaut cadre to teaching an Aerospace Nursing Course at Cape Kennedy to continuing research.

In the midst of all that, in 1961, the school joined the newly created Aerospace Medical Division in a complex at San Antonio. On Nov. 21, 1963, then-President John F. Kennedy dedicated the new complex in what would turn out to be his last public speaking engagement, as he was assassinated within a few hours of leaving.

Despite the school’s countless contributions to space research – the study of cosmic radiation, toxicology standards, and “space food,” for example – only the space training mission would continue by the end of the 1960s. All of the astronauts would continue to do their centrifuge and other training at USAFSAM through the end of the Shuttle program.

During the Vietnam War, the school’s training mission changed and grew along with the number of medical specialists in the Air Force, and research was done to develop courses addressing tropical diseases and aeromedical evacuation. Within that decade, USAFSAM would also pioneer much of what we now call hyperbaric medicine. Researchers at the school created the first image of living tissue, using something called nuclear magnetic resonance (what would mature into the MRI) and learned that a laser could reshape the cornea of the eye with almost immediate recovery (which would be applied later as PRK).

The 1970s and 1980s saw USAFSAM’s focus shift yet again, to emerging aircraft challenges and preventive medicine, including cardiovascular risk prevention and chemical, biological, radiological and nuclear research. Many of the school’s clinical studies also came to fruition, including soft contact lenses, chemical antidotes and fatigue countermeasures.

The Aerospace Medical Division was renamed the Human Systems Division to reflect the changing emphasis, and in 1990 all human research efforts – including that done at the School, as well as the School’s library – was consolidated as part of the Harry G. Armstrong Aerospace Medical Research Laboratory, one of the Air Force’s “super labs.” USAFSAM was dedicated only to training and education for much of the 1990s.

Near the end of the decade, in 1997, the four “super labs” were combined to create a single Air Force Research Laboratory. The school added consultation back into its mission and reacquired the library, which was by then the largest aeromedical library in the world. Around the same time, USAFSAM became the training and development catalyst for Combat Medicine, establishing the Expeditionary Medical Support platform and the Centers for Sustainment of Trauma and Readiness Skills.

The school’s international training program was expanded, and after 9/11 there was an increased emphasis on homeland security and disaster response as well.

As USAFSAM entered the 2000s, the research side of the house developed enhanced bio-markers, refined operational vision assessments and engaged in a multidisciplinary response to questions about the F-22 life support system. On the education and training side of the house, student throughput was at peak levels and the school developed new courses to meet new Air Force demands. There was a renewed focus on the human operator, including the study of how to apply the behavioral and psychological aspects of flight in manned systems to “unmanned” and remotely piloted systems.

In fact, the school and the 311th Performance Enhancement Directorate, along with AFRL’s Human Effectiveness Directorate, together served as the Air Force agents for human-centered research, development, acquisition and operational support. The ever-expanding, continually refined, and often similar missions and research areas of the three organizations meant there was a great deal of synergy to be gained by combining them, and a decision was made in 2005 to do just that.

Three years later, on March 25, 2008, officials at AFRL officially activated the 711th Human Performance Wing at Wright-Patterson. Almost all elements from Texas, including USAFSAM, moved to Ohio over the next several years. At the same time, the school absorbed the Air Force Institute for Operational Health. The school received – and continues to receive – tens of thousands of samples each week from around the globe, making it one of the largest influenza and respiratory disease surveillance activities in the world. The labs play a critical role in global outbreaks such as the 2009 H1N1 influenza pandemic and the Zika virus public health emergency.

Though refined over 100 years, the core of USAFSAM’s original mission continues today: optimize and sustain Airmen health and performance through world-class education, expert consultation and operationally focused research.

To mark a century of operation, USAFSAM will celebrate throughout 2018. The year will include special heritage events as well as a monthly article highlighting a key “exemplar” from the school’s rich history.

About the Author