… and O.J. Simpson.

Really.

It turns out my brother was involved in the promotion of the Juvenile and Foxy Brown concert at Cincinnati Music Hall with OJ as the MC. We know the background. OJ was acquitted in the slaying of his ex-wife, Nicole Brown Simpson, and her friend, Ronald Goldman, in 1995, but a jury in 1997 found him civilly liable in both deaths and ordered him to pay $33 million. He never did, though his estate might.

The Cincinnati appearance was part of an OJ redemption tour for a man who was, arguably, the most controversial and divisive popular figure in America.

You wouldn’t know that in Cincinnati.

My wife and I drove in a limo with a group that included my brother and Norman Pardo, OJ’s then-manager. We met Simpson at the Cincinnati airport, and he walked towards us with a pronounced limp from injuries that occurred during his football days.

He spent the early part of the day doing radio shows. I don’t remember anything about the interviews because they were all laced with talking point pablum and softball questions. But I do remember that everywhere we went, people lined the street and loudly cheered for OJ.

Remember the context. OJ was a flashpoint — still is — in America’s racial divide. Black people applauded his acquittal, while White people literally wept.

So here comes OJ to a city still recovering from the 2001 riots — the worst since Los Angeles in 1984 — spawned when a White police officer killed an unarmed Black man.

OJ’s supporters saw him as a symbol of Black injustice representing a brother who shouldn’t be dead. While several Black celebrities boycotted appearances in Cincinnati, OJ came.

OJ took up the Cincinnati cause, even though he once famously said, “I’m not Black, I’m OJ.” He was what people wanted him to be in the moment, not who he believed he was. Just like in his acting days, he played a role and got paid for doing so.

The small crowd of 1,200 inside the Music Hall cheered, too, especially when OJ said, “Hip-hop has gotten a bad rap. I know all about bad raps.”

Uh-huh.

While the show went on, I talked to OJ backstage and asked if he would collaborate on a no-holds-barred book with no topics off-limits — including his ex-wife’s murder. He said I could write it, and he would cooperate if I could get him a hefty, six-figure advance.

I had phone calls with OJ, his team, and the agent contacting publishers about the proposal I had written.

It quickly became evident that a book about OJ was as popular as the smell of sewage during a wedding party. Seeing the book would go nowhere, I pulled out of the project, which the New York Daily News reported.

People have asked me why I would agree to write a book about such a despicable character. That’s an easy answer. A journalist seeks truth and reports it because how else does society get a window into any distasteful subject? Journalists, including me, interview and write about bad people all the time. We don’t pick and choose stories based on niceties.

After the concert and back at the hotel restaurant, OJ, and my wife and I, had dinner — I paid — when, without prompting, Simpson loudly said:

“I ain’t kill the ...,” and he used a word that rhymes with the snitch.

I found that an interesting way to proclaim innocence.

When I learned Simpson had died on April 10 at the age of 76, I called Pardo and asked him to describe OJ in a sentence.

“That’s a hard one,” he said before adding, “He was a mean and greedy con artist.”

Remember, that’s coming from a friend.

Ray Marcano’s column appears on these pages each Sunday.

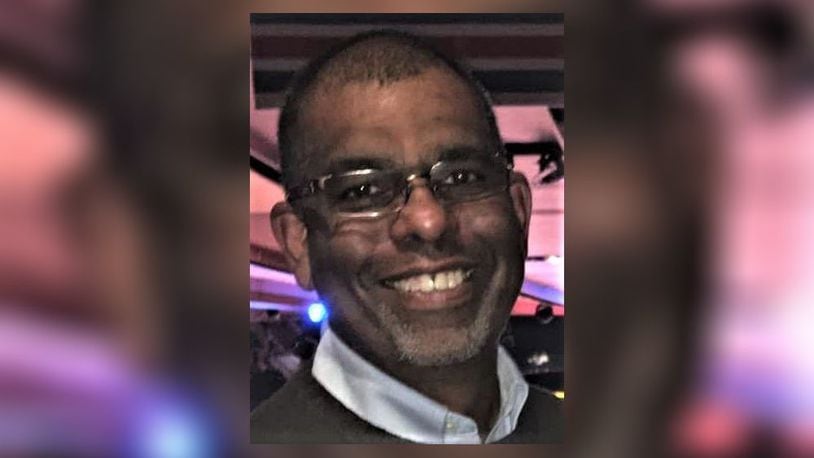

About the Author