But not all the loads the ATTA certifies are military in nature. In fact, ATTLA supports all federal agencies. Probably the most expensive and greatly anticipated loads ATTLA has ever certified safe for flight is scheduled to reach for the heavens a million miles from Earth in 2019.

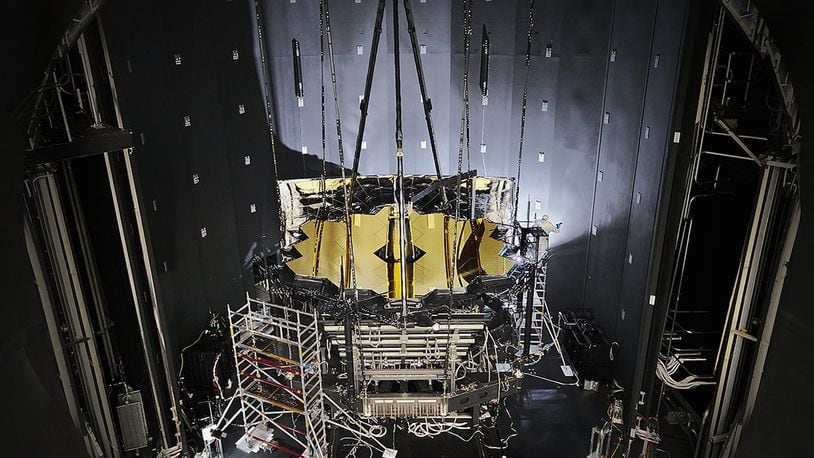

NASA's James Webb Space Telescope, now in production for more than two decades, is 100 times more powerful than the Hubble telescope and will allow astronomers to see deeper into the universe than ever before, according to NASA's website, www.nasa.gov. It is such a scientific and engineering feat that NASA had to invent 10 new technologies just to build the telescope.

Webb is an international program led by NASA with its partners, the European Space Agency and the Canadian Space Agency. Webb will cost about $8 billion to produce, and it will be the largest space telescope to date, according to NASA.

The telescope’s 18 lightweight beryllium mirrors have had to make 14 stops to 11 different places around the United States to complete the manufacturing process. Once combined to form the telescope weighing less than seven tons, NASA had to design a 165,000-pound shipping container to move it around safely the last few stops for final assembly and testing. This custom container had to be made specifically to provide mechanical suspension and a climate-controlled environment with all the necessary sensors for the telescope during air transport on a specially modified Air Force C-5C aircraft, of which there are only two in the Air Force inventory.

ATTLA’s involvement with the James Webb space telescope program began in 2010 when the team was contacted by NASA to provide certification of the NASA Space Telescope Transporter for Air, Road and Sea, or STTARS – the name of the telescope’s shipping container.

“Certification is required for cargo or equipment that is bigger or heavier than certain criteria in order to minimize the loading and unloading effort, describe the ability to restrain the load inside the airplane, and to certify that the cargo will be robust enough to withstand air turbulence or hard landings,” said Mark Kuntavanish, Air Transportability Test Loading Activity, lead engineer. “We issue a certification that says, ‘If you follow these instructions, this item is cleared to be airlifted.’”

The ATTLA also maintains a database so that transportability agents in the field who are responsible for arranging shipment of cargo can go online 24/7 to determine if an item has been certified for airlift or airdrop, Kuntavanish said. The ATTLA has issued more than 7,000 certifications since the mid-1970s.

ATTLA’s John Andersen was appointed lead project engineer for the STTARS certification in 2010, working on the project until certification was issued May 15, 2014. In order to certify the shipping container for transport on the Space Cargo Modified C-5, the aircraft and the STTARS were both brought to Wright-Patterson Air Force Base from Nov. 15-17, 2012, with actual loading and unloading being conducted, Andersen said.

“NASA had created manuals on how to do this, and our effort was to test whether the manuals worked, and they didn’t,” said Andersen. “We had to extensively change how the container would be loaded and unloaded.”

The container was very low to the ground – less than a foot, Andersen said, adding that additional ramps allowed for a shallow enough approach angle so the container could clear the ramp area and the tail when being loaded.

“After loading the shipping container, there were only about six inches remaining on each side,” Andersen said. “To steer something over 100 feet long was a huge challenge. So we had to figure out a method to line it up correctly to minimize the steering. Cameras were used, but we kept having trouble because of distortion between the monitors and the cameras,” Andersen said.

The ATTLA team had only a limited amount of time to perform the loading and unloading test procedures that would be required to issue the certification. Some old-fashioned ingenuity came into play when Andersen suggested a low-cost option to ensure the load would be lined up appropriately within a half-inch of the centerline of the aircraft.

“I threw out an idea – why don’t we go to a local home repair store and get a laser guide that could shine both along the floor of the aircraft’s centerline and centerline of the container’s back side so we could align the load? It was getting dark, so the team thought that was a good idea. So, for about $70, we bought the laser guides, set them up, and we were able to load the container perfectly by following the laser lines. Once we did this, it went smoothly,” Andersen said, adding, “Loads run out of volume of space faster than they reach the weight limit.”

Andersen was on the site non-stop for 22 straight hours during the testing procedure and said it took 140 chains, each weighing about 26 pounds and rated to secure up to 25,000 pounds, to tie the load down properly.

Working closely with the AFLCMC System Program Offices and avionics experts, the ATTLA team also evaluated the container for interference with aircraft systems and whether the aircraft systems would interfere with the spacecraft systems to make sure nothing malfunctioned during flight.

“I’m glad we came up with a cheap solution to load the container on the aircraft using the lasers,” said Andersen. “It didn’t cost thousands of dollars to do it or a lot of time.”

“The whole thing might have had to be scrapped if we couldn’t load it that afternoon and had to start back at square one,” Kuntavanish said. “Sometimes a little practicality and cleverness pays off.

“What’s neat about our job is that we are exposed to such a variety of science and engineering disciplines. Sometimes its thermodynamics, with gas expansion and rapid decompression to electrical, to structures, mechanical engineering, hydraulics, grease, hazardous fumes or even biology,” said Kuntavanish.

If all goes as scheduled, the James Webb Space Telescope will launch on an Ariane 5 rocket from a European launch complex located near Kourou, French Guiana, in 2019, NASA’s website says.

About the Author