In 1898, young James Cox bet his wad on a losing horse - the Dayton Evening News.

At its best, fish wrap. At its worst, a money pit for banker and News owner Charles H. Simms - who, with his paper up for sale, must have been thrilled by the appearance at his door of a wide-eyed, would-be newspaper tycoon with dreams of becoming another Joseph Pulitzer.

For his foundering paper - with its meager staff, rickety equipment and equally rickety finances - Simms wanted $26,000. He had no takers until Cox came along.

Cox was 28, too young to be running a newspaper and lacking the capital to meet Simms' asking price. So Paul Sorg, a recently retired Middletown congressman and Cox's former boss, put $6,000 into Cox's pocket and lined up local investors to buy stock in the new venture.

Simms sealed the deal with Cox on Aug. 15, 1898. Like most publishers who bought papers in the burgeoning era of muckrake, Cox changed his new acquisition's name. His Dayton Daily News debuted unceremoniously a week later, on Aug. 22.

The competing Dayton Journal hit the streets with a prediction of Cox's demise: "The Evening News has been sold and will hereafter be a Democratic paper. Democratic papers have never paid in Dayton and never will. Four of them have failed."

At first, Cox's new adventure must have seemed more a nightmare than a dream come true. Subscribers were scarcer than Cox had been promised; when he set out to find the 7,500 he thought were on the books, he could locate only 2,600. The News' ledger ran red for several years; even if Cox filled every column with advertising, said the bookkeeper, the News would still lose $500 a week.

But the young publisher was undaunted. He had a newspaper of his own.

Cox the journalist

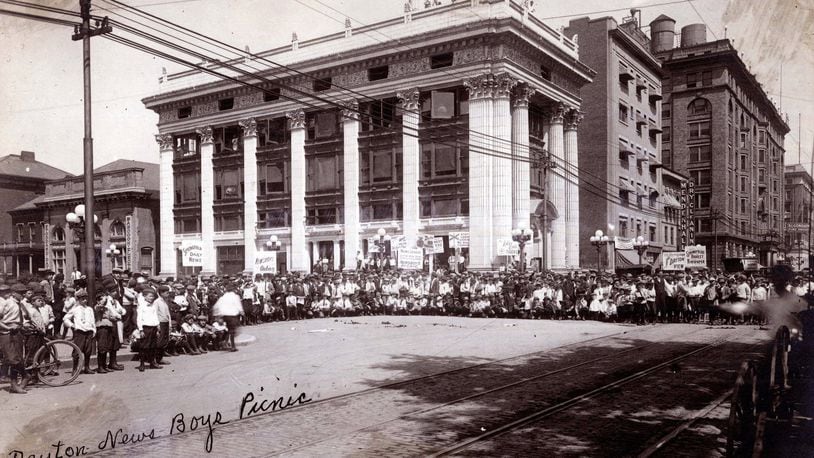

Credit: Dayton Daily News Archive

Credit: Dayton Daily News Archive

Born on March 31, 1870, Cox was the youngest of seven children. He was self-taught, an avid reader of literature, biography and history who left school at age 16 after being raised on the Old Home Farm, his family's Jacksonburg homestead in Butler County.

Before he was 20, printer's ink had moved into his blood. A schoolteacher during the week, Cox was a newsboy on Saturdays, delivering the entire circulation of his brother-in-law's Middletown Weekly Signal. In 1892, the Cincinnati Enquirer hired him as a copy reader on the telegraph desk. Before long, he was out on the streets, chasing spot news and learning all he could about the city.

Cox was a shrewd and enterprising reporter. When a train wrecked near Middletown early in his Enquirer career, he ran first to the local telegraph station and asked the operator to send the telephone directory over the wire to the Enquirer newsroom, thus tying up the first-come, first-served wire and preventing other reporters from filing their stories first. In the meantime, Cox raced back to the wreck, got the story, then returned to the telegraph station to file his own piece. It was one of many scoops.

Before long, his relentlessness got him in trouble at the Enquirer. A railroad magnate, displeased with Cox's reporting of his business deals, convinced Cox's editor to get rid of the young man. Outraged but obligated to support his wife, pregnant with their first child, Cox jumped at the chance in 1894 to become an aide to Middletown Congressman Paul Sorg, who was heading to Washington, D.C. Cox spent three eye-opening years in the capital, returning to Ohio in 1897 with a fire in his belly for the newspaper business.

"The most fortunate circumstance in my life was the selection of Dayton in which to ... operate a newspaper of my own," Cox wrote later.

Building a newspaper

Business, like journalism, came easily to Cox. Righting what was wrong with his fledgling paper was his passion. He was a true workaholic: "I read all the copy, looked after make-up, answered the business correspondence and kept an eye on details, writing my editorials after dinner at night," Cox wrote in his 1946 autobiography. At one time or another, he served as editor, reporter, circulation manager, ad solicitor and business manager.

A fan of newspaper icon Joseph Pulitzer, Cox knew he had to change virtually every aspect of the News to birth a newspaper that was truly metropolitan with great mass appeal, and not a mere political-party sheet.

So change everything is what he did.

Women? Cox paid attention to their interests, snagging even more female readers after he hired Dayton's first woman's page editor for his new society section.

Stock market quotes? Cox made them timely - and thus more sought-after by readers. Later, he expanded to a full market page, with stock-exchange, grain and livestock tables.

A part-time Associated Press wire service? Cox bought full-time double AP wire service in 1901 so the News could have more national, international and sports news than its competitors.

Art? Illustrations were O.K., but Cox knew photographs would fascinate, and got them in print. The News' first photographs were produced from chalk plates.

He also ran book serializations and inserted McClure's Saturday Magazine supplement. Readers in outlying communities were drawn to Cox's suburban columns, which became a regular feature.

Seasonal advertisements out of season? Cox banned them, then changed the rules. One of his first deals was with Dayton's Rike-Kumler Co.: If Rike's ran half-page ads for 90 days, prepared by a full-time ad man, and they brought results, Rike's would pay the newspaper at regular rates. If Rike's didn't get worthwhile results, Cox bargained, the ads would be free. Rike's bought Cox's plan, watched in amazement as fresh advertising generated business and soon became one of the News' largest advertisers.

Cox reached out beyond Montgomery County. A year after buying the News, Cox was distributing it in Xenia, Piqua and Greenville. He fought a bigger circulation battle to the south, as he slowly lured Dayton readers away from the Cincinnati papers.

Knowing that technology would get him everywhere faster, Cox bought a triple-deck, gasoline-powered press, nudged deadlines back two hours and still got fresher news on the streets faster than the competition. By 1900, the News had become the leading paper in Dayton, and Cox had made enough money to buy out his investors of 1898.

He was, at last and unquestionably, the boss.

Hell-bent on boosting circulation, Cox continued making changes in the News at a frenzied pace. And then came the crusades.

When he discovered that Dr. Joseph E. Lowes, a Republican Party boss who dominated Dayton politics, was involved in finagling some government deals that profited his own company, Cox publicized Lowes' practices. In the process, Cox portrayed himself as a crusader for the people; the News he christened as "the people's paper."

The Cox-created scuttlebutt made Daytonians take note. Later, Cox admitted culpability in the libel suits Lowes filed against him, but the $1 judgment against him was ironic in the face of what he and his paper had gained: more readers.

"There were stirring times," Cox wrote in 1948, reflecting on the News' first 50 years. "Publishers without backbone have wilted before their vociferous fronts. I would be less than frank if I did not say that I enjoyed these experiences, because every one of them through their accruing results told us that regard for the general welfare, rather than for selfish interests, paid handsome rewards."

In 1907 Cox went head-to-head with John H. Patterson. Cox never worried about making enemies, even if that enemy happened to be the powerful founder and president of Dayton's National Cash Register Co.

Patterson, who later faced federal indictment for antitrust violations, had just learned that only bribery would get him a new railway spur for NCR. Enraged, Dayton's leading businessman called a meeting of 1,000 civic leaders, lost his temper, complained about the corrupt element in the city and said he was moving NCR out of Dayton.

Cox couldn't resist Patterson's taunt. So he ran an ad poking fun at Patterson and his famous meeting.

Daytonians, worried about the possible move, were appalled at the News' stance. When an NCR worker died after being thrown from a horse during a training session mandated by Charles Palmer, Patterson's personal trainer, Cox took up where he'd left off, accusing Patterson of being under Palmer's spell.

Patterson spent so much time battling Cox in court that he closed down NCR for a short time while he pursued his quarry. Cox's attorney, in the meantime, was preparing for the trial. After being questioned by this attorney just days before the trial would have begun, Patterson gave up, dropped his lawsuits and paid Cox's legal expenses. It's unclear just what they discussed.

"I had a great liking for Dayton and was outraged by the unwarranted attack upon it and its citizens," Cox wrote later. "I could not dismiss the conviction that it was the duty of our newspaper to stand by the community regardless of consequences."

Toward a media empire

By 1903, the Dayton Daily News had become a business success. Two years later, with annual profits equaling his original purchase price, Cox had put his chief competitor, the Dayton Press, out of business. He celebrated by buying the Press' equipment - and the Springfield Press-Republic, which he renamed the Springfield Daily News. In 1908, Cox's attention was diverted to politics. By then the News had a circulation of about 20,000 and was recognized among the 100 best newspapers in the country.

He was elected to Congress in 1908. He was elected Ohio's governor in 1912 and 1914. After losing the 1916 gubernatorial election, he won the governor's seat again in 1918, Ohio's first three-time governor. Much of his progressive legislation became law, including school, tax and prison reforms as well as a landmark workmen's compensation bill.

Cox reached the pinnacle of his political career in 1920, when he won the Democratic nomination for president. His Dayton Daily News staff sent him a huge bouquet to congratulate the man they had routinely called "the Governor' since 1912.

As a politician, Cox participated in many major historical events, meeting many of the diplomats, leaders and statesmen of the day: people like Woodrow Wilson, Harry S. Truman and Franklin Delano Roosevelt - Cox's 1920 vice presidential running mate, who became president in 1933, working from the springboard into national politics he'd gained from campaigning with Cox.

But first and foremost, Cox was a newspaperman; when he lost the presidential election in 1920 (to another Ohio newspaperman, Marion Star publisher Warren G. Harding, of the G.O.P), he was neither desperate nor despondent. "I had this great advantage," Cox wrote later. "I was still in public life. I had my newspapers."

Cox never again ran for public office, instead plunging back into the newspaper business. Back in Dayton, he added an annex to the original Daily News building in 1922 to house new presses, editorial rooms and offices. In 1956, a six-story building was attached to the original 1910 office. Here Cox housed the Dayton Daily News and The Journal Herald, which he created in 1949 after having bought The Journal and The Herald the year before.

But by the time he got to The Journal Herald, Cox was used to buying papers. In 1923, he had bought two: the Miami Metropolis in Florida, which he renamed the Miami Daily News, and Ohio's Canton Daily News, which he later sold. He bought the Springfield Morning Sun in 1928; the Atlanta Journal in 1939; and the Atlanta Constitution in 1950. That year, his worth was estimated at $40 million.

The people's paper

Cox's success during his first 10 years of running the Dayton Daily News allowed him to expand his local news staff, who began bringing readers stories about Dayton's industrial and suburban development. Cox, who believed his newspaper should lead change, sometimes dedicated an entire page to opportunities in the Miami Valley.

"Wherever there was a Cox paper there was a Cox influence," inventor Charles F. Kettering once said. It was true: Cox saw his papers as a way to educate and influence the masses. He maintained that the quality of life and conditions in Dayton could always be improved, and he used his press to advocate what he thought should be done, and arouse the public into supporting community reforms.

Still the politician at heart, Cox wanted the public's confidence. Without it, he knew, the News could not grow.

"If a reader picks up a paper and after perusing its columns finds that the germ of discontent or pessimism has been wafted away, he is certain ... to develop a sort of affection for it," Cox wrote in 1923.

But doing what he could to waft away the germ of discontent could also put him in occasional conflict with another of his oft-stated principles, that of holding steadfastly to the truth. "If public opinion has an untruth fed to it," Cox once said, "it will be just as harmful as though we had deadly poison in our drinking water."

In the wake of the 1929 stock market crash, for example, Cox ordered all his papers, including the Dayton Daily News, to keep stories about the crash off the front page. News of Cox's mandate made the wire. Cox had little trouble justifying the difference between absolute truth-telling and bolstering public confidence; he told the Associated Press he made the decision with the best interests of the community at heart, since stock buying was an "incidental thing' in the life of the country: "(The crash) is nearly if not quite over and yet all of our newspapers are filling the public mind with the idea of disaster. This can easily develop a psychological condition hurtful to the general interest. The great masses of the people who are not involved can pursue, uninterrupted, their part in commerce. Otherwise, the impression will grow that we are on the verge of a serious industrial depression. My thought as publisher was to help our public forget the panic ..."

The people's publisher

In spite of his accumulated wealth and prestige, Cox remained in touch with the common people. Governor of Ohio during the 1913 flood that devastated Dayton, Cox directed rescue and relief efforts, calling on his governor friends to garner what supplies they could to save the city and help it rebuild. In 1914, Cox signed into law the contested Ohio Conservancy Act, which put Dayton on course to safety from future floods.

During the Depression, Cox took care of his own. Carl Beyer remembered former city editor Herb Koehl telling him about the Governor's soft side. "During the Depression, ad sales were on straight commission," Beyer said. "There were not a lot of ads being sold, so the Governor told the ad people, "This Depression isn't your fault; from here on, you're on straight salary." It wasn't until the '60s that they went back on draw and commission."

Beyer said Cox also instituted a policy of unlimited sick leave.

"The Governor believed when a person is ill, the last thing he needs to be worried about is who will pay his medical bills, or how he'll be able to support his family," Beyer said.

Great expectations

Rare was the publisher who was also a great editor. Cox was both. Never did he lose interest in the daily details of running the News, or of any paper he owned, always keeping a firm hand on the editorial and business sides. Roz Young recalls a day when the Governor called the editor of every page at the Daily News and bawled them out for any number of offenses. "Gave 'em hell," she said.

Sam Rubin, a member of the News' editorial staff for nearly 45 years, remembers seeing the Governor come and go, getting off the elevator and going into his office with his big cigar. "Sometimes he would phone the desk and ask questions about some current event, and you had better be ready with the correct answer and the details," Rubin said.

Jim Nichols, who joined the News as a full-time sports reporter in 1940, said Cox had his finger into everything. "He would stop, walk into the newsroom and see what was going on. He was the personality of the Dayton Daily News."

And yet, surprisingly, many long-time News employees believed the Governor seemed awed, almost humbled, by how large his enterprise had grown. Said Rubin: "One day he came out and looked the place over and he said, "Do all these people work here?''

A long and happy life

Cox died on July 15, 1957, at the age of 87 after suffering a series of strokes that began at the News building.

Roz Young was just coming into the building. "Everybody was standing around talking ... people were sorry because they felt he was a great man. There was genuine sorrow over his death."

In his will, Cox set down that his newspapers should remain devoted to the working people, since they bought and read the paper. Once, reflecting on what he might become after this life, Cox mused not about the political prowess that had taken him from the halls of the Capitol to within a few steps of the White House, but about being a newspaperman.

“If there is anything in the theory of reincarnation of the soul,” Cox wrote, “then in my next assignment, if I be given the right of choice, I will ask for the aroma of printers ink.”

About the Author