Mary Fields was the first African-American woman to deliver mail by stagecoach in the United States. Under contract with the U.S Post Office beginning in 1895, her route was through the rocky terrain of Montana.

She was 6-feet tall, weighed 200 pounds, played cards at the local saloon, and had a standing wager that she could knock out a man with one punch.

Michael Carter is a college man.

He’s the senior advisor to the president at Sinclair Community College and the school’s Chief Diversity Officer. He once was the head basketball coach at Springfield South and Trotwood Madison high schools.

He is one of the key people helping put on Wednesday’s Joe Morgan HBCU Classic matching Wilberforce University’s baseball team against Kentucky State, both Historic Black Universities, at the Cincinnati Reds Youth Academy on Seymor Avenue.

The game, orchestrated by the Cincinnati Reds, honors the legacy of Jackie Robinson, whom Major League Baseball celebrated Monday.

Carter and Stagecoach Mary would seem to have nothing in common, but that’s not quite the case.

They both have Ohio roots. She was raised by Ursuline nuns in Toledo. He grew up in Springfield’s East End.

A few days ago, they both shared the stage at the Dayton Regional STEM School on Woodman Drive.

Carter was there giving presentations to high school classes as part of the school’s first annual Culture Fest.

She was there in an old photo he brought along. It showed her in a long dark outfit, with a knit cap on her head, a rifle cradled in her arms and her dog lying at her feet.

But the real thing Mary Fields and Michael Carter share is their ability to deliver a powerful message to others.

There’s a story of the day Mary was playing cards when she suddenly looked up, saw a guy who owed her $2 and decided it was time to collect.

The guy had stiffed her on some laundry work she’d done for him, so she followed him outside, had a few words and preceded to knock him out…with one punch.

She returned to the table, picked up her cards and announced:

“His bill is now paid!”

Carter was at the school to talk about African American contribution and accomplishment and his compelling examples and colorful tales caught the attention of the high school students.

In Mary’s story – the cigars, cards, and fisticuffs – were just window dressing. The real lesson was about an independent woman who held her own in a macho setting and – as the story would later reveal – was admired and beloved by everybody from the townsfolk and those on the stagecoach line to the Ursuline nuns.

She was so popular in the town of Cascade, Montana, that schools closed every year on her birthday. When her house burned down, townspeople rebuilt it for free. And when she died in 1914, her funeral was the biggest the region had ever seen.

Carter specializes in presenting forgotten or under-told stories from the diverse tableau of humanity, especially people and moments tied to Black history. And that’s why he’s involved in Wednesday’s baseball game.

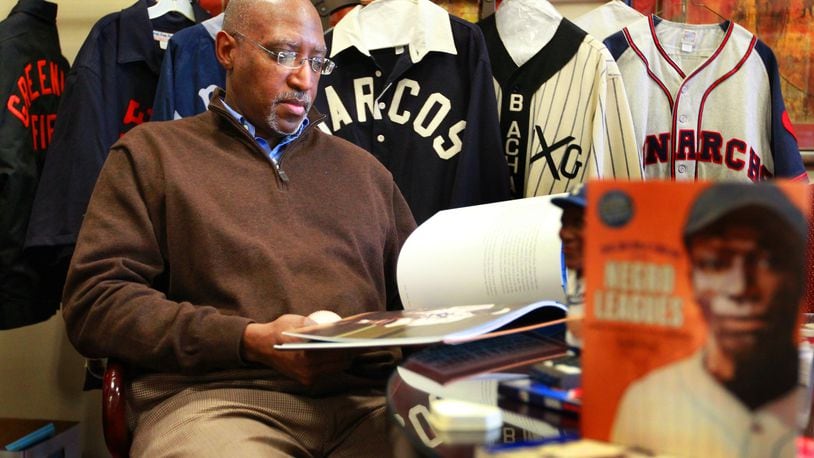

Both teams will play the game in different recreated Negro League jerseys that are part of the extensive collection Carter and his older brother Darnell, a prominent Springfield attorney and educator, have assembled over the years in what truly has become a labor of love for both men.

Negro Leagues appreciation

Carter became interested in the Negro Leagues when he was growing up on Lexington Avenue in Springfield.

“A man who lived two doors down Mr. Ballard had played in the Negro Leagues,” he once told me. “He was a postman and the most pleasant man in the world. But he’d never watch a Major League Baseball game. He was bitter over all that and wouldn’t talk about it much. But my dad told me stories.”

The segregationist stance of big-league baseball gave birth to the Negro Leagues in 1920 when Rube Foster brought representatives from eight teams — including the Dayton Marcos — to Kansas City for an organizational meeting.

The Marcos played their first Negro League game against the Chicago Giants at Westwood Field on what is now James H. McGee Blvd.

That’s four months before the Dayton Triangles played their much more celebrated first game against the Columbus Panhandles at Triangle Park.

It’s recognized as the first-ever NFL game and that’s turned Triangles into a communal treasure.

The Marcos — who debuted in Dayton at a time when Blackss were barred from many hotels and restaurants in the city — moved to Columbus after a season, returned to Dayton five years later, and eventually became a barn-storming team that was mostly forgotten.

Two of the Marcos most famous players — pitcher WG Sloan, a hero during the 1913 Dayton flood; and Ray Brown, a National Baseball Hall of Fame enshrinee once considered the best pitcher in the Negro Leagues — were buried in unmarked graves in Dayton for over four decades.

Eight years ago, Carter hatched the idea of young college players learning about the Negro League past and floated the idea to then Sinclair baseball coach Steve Dintaman about his players wearing the jersey collection in a game.

Sinclair became the first college team in the nation to wear Negro League jerseys in competition. That happened three years in a row until Sinclair suddenly dropped all sports.

Kentucky State had been one of Sinclair’s rivals in the game and Thorobreds’ coach Rob Henry told Carter his team would like to continue the tradition.

In 2022 the Reds got involved and Kentucky State played a doubleheader against Spring Hill, with both teams wearing jerseys of teams like the Chattanooga Choo Choos, Indianapolis Clowns, Kansas City Monarchs and yes, the Dayton Marcos.

Last season Kentucky State was pitted against Wilberforce, which – thanks to a partnership with the Cincinnati Reds and the Reds Community Fund – had resurrected its baseball program that had been defunct since 1947.

In a game Carter described as “pitching and defense optional,” Kentucky State edged the Bulldogs 19-18, in front of a packed house.

Wednesday afternoon the two teams meet again. Wilberforce has a 7-22 record and Kentucky State is 16-23.

The Reds will have an exhibit at the game that includes Negro League artifacts and, like last year, Ken Griffey Jr., in conjunction with Nike baseball, is scheduled to give participating players limited edition Ken Griffey Jr. cleats before the game.

They’re Dodgers blue and have Jackie Robinson’s No, 42 on the side.

Carter said the college players look forward to taking part in this game and in the process have learned a little about the Negro Leagues.

Powerful presentation

That’s what Carter’s efforts are about these days.

During his presentations to the STEM School students, he touched on everything from the Tulsa Race Riot of 1921 to the Kentucky Derby’s Black jockeys and how 16 of the first 28 winning riders were Black.

He introduced DeFord Bailey — the “first star of the Grand Ole Opry” — who was Black. And he talked about philanthropist Julius Rosenwald, the Jewish leader of Sears and Roebuck, who was responsible for the construction of 5,000 schools and shops in the South for African American children and homes for their teachers.

He showed a photo of two-year-old Dave Chappelle and his three-year-old brother Sedar meeting Muhammad Ali in his hotel room after the heavyweight champ’s workout for his upcoming bout with challenger Jimmy Young in Landover, Maryland, in 1975.

But the picture that turned the most heads was one of an escaped slave named Gordon who he called “The George Floyd of 1863.”

Gordon had been viciously whipped on a Mississippi plantation and eventually escaped and made a harrowing 10-day trek to Baton Rouge, which was under the control of Union troops. To keep the pursuing bloodhounds off his scent, he rubbed onions over his body.

When he finally was safe, he volunteered to fight in the Civil War, as would 200,000 other Blacks.

Once he shed his shirt for his physical, the bubbled welts and scars that covered his back were discovered.

Two itinerant photographers who were there took photos of him that were published in Harpers Weekly and turned into postcards.

“That image forced Southerners to pause the lie they circulated that slavery wasn’t that bad,” Carter said. “And Northerners who were never around slavery suddenly understood what it was.” As he recounted the tale, Carter had the rapt attention of those in front of him.

He delivered his message just as powerfully as Stagecoach Mary had to the guy who had refused to pay his bill.

She did it with a punch, he did it with a plea:

“People my age have a lot of crazy ideas. We need your brightness and optimism to help us. I depend on young people like you to save us.”

About the Author