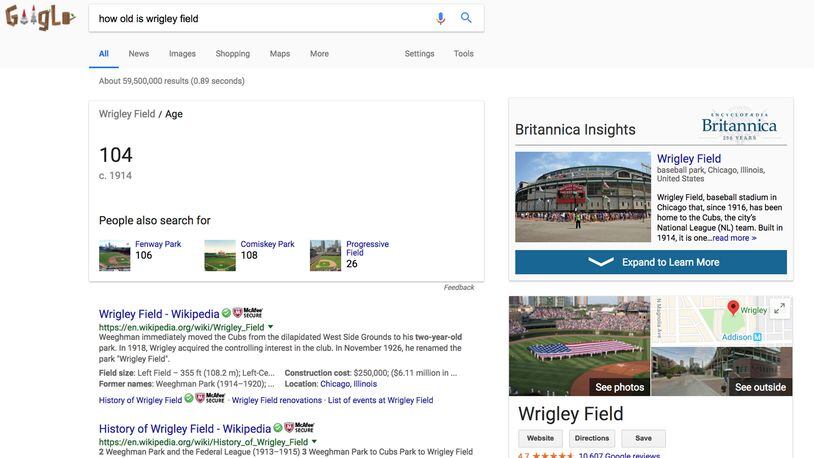

Google the depth of Lake Michigan and the extension, called Britannica Insights, offers up the encyclopedia’s entry on the 923-foot-deep Great Lake. Search for the age of Wrigley Field and just to the right of the top search result — 104 years — is Britannica’s entry on the Cubs’ home.

The idea is to combat the common habit of reading just the top Google results and accepting that as fact, said Karthik Krishnan, global chief executive officer of the Britannica Group, which owns Encyclopaedia Britannica. People place the desire for quick answers above the need for truth, Krishnan said.

“(My kids) ask a question, they get an answer, they walk away. They don’t pause for a second to think, ‘Is that true?’ “ he said. “Critical thinking is missing in this world and part of the reason is we are dependent on technology.”

Unverified information runs rampant online, and Encyclopaedia Britannica hopes to be a credible resource and “help people easily cut through that clutter,” Krishnan said.

Britannica is banking on its brand cachet as a 250-year-old institution for providing verified information. But Northwestern University professor Brian Uzzi, who has studied how people consume information and behave on social media, said the success of the extension will depend on whether internet users still see the company as a bearer of truth.

“They lost that,” said Uzzi, who teaches at Northwestern’s Kellogg School of Management. “Why would you use their … Chrome plug-in when you probably think Google is just as accurate?”

Still, adding a layer of information could be helpful for a population that tends to blindly accept the info they see online as truth, he said. Most people don’t know that Google ranks its search results on relevancy and utility. Seeing dissenting information from Britannica could start a conversation.

The proliferation of what has been dubbed “fake news” came to a head after the 2016 presidential election, when it came to light that some political stories circulated on social media were fabricated. Now some Americans question which sources they can trust.

The election also brought attention to another social media habit. Internet users tend to click on and read stories or posts that affirm beliefs they already hold, Uzzi said.

Britannica Insights will not fact-check news stories, but rather provide people with a verified source they can quickly and easily identify, Krishnan said.

The feature also could help Britannica gain some ground on Wikipedia, the free online encyclopedia that anyone can edit. Last month, an anonymous user added the word “Nazism” to the California Republican Party’s Wikipedia page entry. Google blamed vandalism at Wikipedia for search results that last month indicated “Nazism” was one of the California Republican Party’s ideologies.

Encyclopaedia Britannica, once known for adorning library shelves with its volumes of reference materials, created its first digital encyclopedia in 1981. Eight years later, it created its first multimedia encyclopedia on CD-ROM. (The company had to include a VHS tape that taught consumers how to use CDs, Krishnan said.) Britannica Online launched commercially in 1994.

The company, which employs about 170 people in Chicago, makes money through subscriptions to its articles and resources — from consumers and institutions like schools — and ad revenue.

About the Author