I was 7 years old, and my family lived just outside of Denver, Colorado. My father was an air traffic controller at Denver Stapleton Airport at the time.

I remember him talking about how they were closely monitoring a volcano out west and the potential to disrupt air travel. While I was too young to know where this volcano was, I do remember being a bit fearful, as I could see large mountains just to the west of where we lived. Granted, those weren’t the mountains everyone was worried about.

On the morning of May 19, 1980, I remember waking up and going outside to see what I thought was snow on the ground, but it looked a bit weird. It turns out, it wasn’t snow, but it was ash from Mount Saint Helens, which had erupted the day before.

In the days that followed, ash was detected by measuring systems 2,000 miles away in New England.

I remember that summer, my family took a family vacation up to the Pacific Northwest. Even though it was nearly 6 weeks after the eruption, many roads were still closed due to mud and debris flows that had occurred.

Plus, there was still a search for some of the 57 people that died from the eruption. It was certainly something I will not forget.

According to the Ohio Department of Natural Resources, Ohio once had volcanoes. However, that was a long time ago. ODNR says the last volcanoes in Ohio were doing the Paleozoic era, some 600 million years ago. Today, any signs of Ohio volcanoes are buried under anywhere from 2,500 to 15,000 feet of rock.

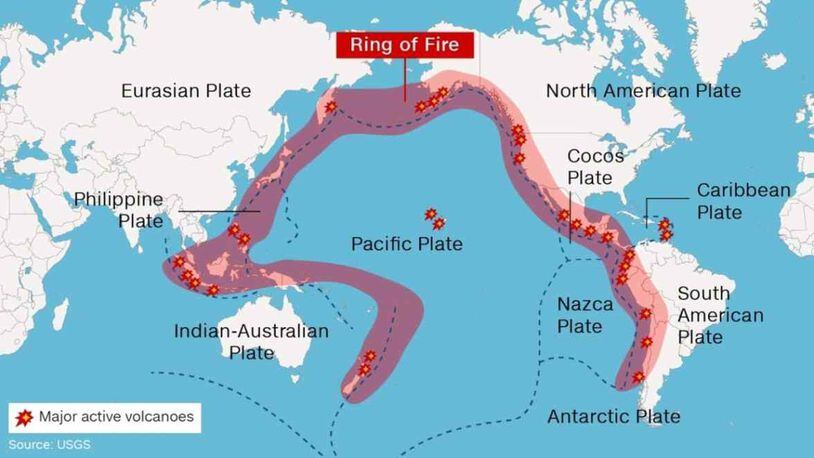

Current volcanoes can be found on the West Coast, which is home to an 800-mile chain of 13 volcanoes from Washington state’s Mount Baker to California’s Lassen Peak. They include Mount St. Helens along with Mount Rainier, which towers above the Seattle metro area and is considered one of the most dangerous volcanoes in the world. This is due to its close proximity to large populations of people and amount of glacial ice nearby that would create massive floods.

The good news is that the West Coast volcanoes are all considered to be dormant. However, the United States Geological Survey (USGS) does say they are still “alive” and must be monitored for future activity. Mount Rainier is believed to have last erupted in 1894. Mount Saint Helens had smaller, minor eruptions in 2004 and again in 2008.

Recently, a much more active volcano has been in the news. While it is a much different type of volcano, the impact of Hawaii’s Kilauea volcano has been devastating to some areas.

Kilauea is a “shield volcano,” the kind that spew lava that is comparatively thinner and runnier than other types of volcanoes, and thus tend to be a bit less dangerous. Mount St. Helens, on the other hand, is a composite volcano, or stratovolcano, a term for steep-sided, often symmetrical cones constructed of alternating layers of lava flows, ash, and other volcanic debris.

Kilauea has a slow, yet still deadly lava flow, but can easily be outrun. Composite volcanoes tend to erupt explosively and pose considerable danger to nearby life and property.

Volcanoes also can impact weather locally and occasionally on a global level.

Following the 1991 eruption of Mount Pinatubo in the Philippines, cooler than normal temperatures were recorded worldwide as the eruption sent fine ash and gases high into the stratosphere, forming a large volcanic cloud that drifted around the world. The sulfur dioxide (SO2) in this cloud — about 22 million tons — combined with water to form droplets of sulfuric acid, blocking some of the sunlight from reaching the Earth and thereby cooling temperatures in some regions by as much as 0.5 degrees Celsius.

A similar phenomenon occurred in 1815 with the cataclysmic eruption of Tambora Volcano in Indonesia, the most powerful eruption in recorded history. Tambora’s volcanic cloud lowered global temperatures by more than 5 degrees Fahrenheit. A year after the eruption, most of the northern hemisphere experienced sharply cooler temperatures during the summer months. In parts of Europe and in North America, 1816 was known as “the year without a summer.” It was reported that snow fell in Ohio at least once in every month that year.

Kilauea’s recent eruptions have impacted the local Hawaii weather with reports of dangerous “vog.” Vog is a form of air pollution that results when sulfur dioxide and other gases and particles emitted by an erupting volcano react with oxygen and moisture in the presence of sunlight.

There have also been reports of acid rain due to the sulfur dioxide mixing with rainfall. However, it is unlikely there will be any major impacts from Kilauea outside of the region. While Kilauea has been in nearly a continuous state of eruption for over 30 years, the volcano typically doesn’t inject much ash or other material into the high atmosphere or stratosphere. Most of the material falls out of the sky before it can have a more widespread impact.

Stratovolcanoes, such as the ones along the West Coast, post the biggest threat to significant weather or climate impacts. However, global impacts from even the worst volcanoes typically would not last more than 1 to 3 years, as the particulate matter injected into the atmosphere would eventually fall back to earth.

Despite Kilauea’s low risk of any global impact, this volcano has had some surprises over the last few weeks. Scientists are closely monitoring this volcano for any larger-scale impacts.

About the Author